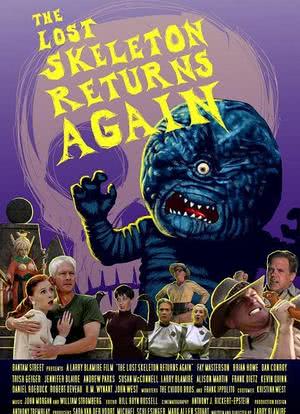

The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra won over B-movie fans with its spot-on parody of ’50s creature features. Now the 2001 indie comedy has spawned a sequel, The Lost Skeleton Returns Again, that once again turns an affectionate eye on early sci-fi and horror flicks, those low-budget gems that continue to charm audiences that have a taste for their unique mix of nostalgia and bizarre humor. The Lost Skeleton Returns Again, which screens for the first time Nov. 9 in Los Angeles, was shot in 12 days with a bigger cast than Cadavra’s and more than 10 times the original’s meager $40,000 budget. Cadavra writer, director and star Larry Blamire reprises those duties for the movie’s more-ambitious sequel, once again playing disillusioned, skeleton-battling scientist Dr. Paul Armstrong. The story picks up two years after where its predecessor left off, as old friends and new enemies schlep into the dreaded Valley of the Monsters in search of yet another rare element, according to the movie’s press materials. Boston native Blamire said the original Lost Skeleton emerged out of a simple question: Could you make a movie for $40,000? My wife (Jennifer Blaire, Animala from Lost Skeleton, photo below) and I moved to Los Angeles to work for an internet company, Blamire told. But we arrived just in time for the internet bubble to burst. So, we’re living in L.A. and wondering what to do next. What do we do? We had no safety net. Blamire was discovering digital video and wondering if he could make a movie on the cheap. Scraping together $40,000 from internet work and turning to a collection of friends he’d made in Los Angeles, he settled in to write, direct and edit The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra. The end result was a bargain-basement cult classic. At a time when independent film is often code for arty, modest-budget, studio movies, Cadavra was genuinely independent — made on an extremely low budget and shopped at film festivals until it landed a well-earned distribution deal. After the movie’s surprise success, Blamire and his crew put in place a system that mimics the one employed by makers of the early Disney movies, pouring money made from one production into the next until there’s a flowing pipeline of flicks. Their starter movie was something of an unlikely foundation upon which to build a Hollywood empire. In Cadavra, a complete set of ’50s cinematic cliches collide — with cheap effects to match. We used a med school skeleton during the production, and it slowly deteriorated over the course of the shoot, Blamire said. We were running around Bronson Cave [better known as the 1960s Bat Cave entrance] on the sly, carrying bones and trying to reassemble the body. Cadavra tells the story of a scientist, Armstrong, who heads out to the woods with his wife, Betty, to do science with the rarest of all elements, Atmospherium. The pile of bones referenced in the title needs the same mineral to return to life, and two aliens from the planet Marva (yes, they’re called Marvins) also need Atmospherium, to fuel their spaceship. According to genre film devotee Dan Madigan, Blamire’s inspirations hark back to the films of Sam Arkoff, Jim Nicholson and Sam Katzman. To call some of those period films shamefully neglected may be stretching it a bit, Madigan said. He rattles off directors like Edward L. Cahn (Invisible Invaders, Creature With the Atom Brain), Richard E. Cunha (Frankenstein’s Daughter, She Demons), Gene Fowler Jr. (I Married a Monster From Outer Space, I Was a Teenage Werewolf) and Herbert L. Strock (How to Make a Monster, Donovan’s Brain) as creators of similarly influential flicks. These early sci-fi and horror moviemakers fascinated and frightened teenagers more so than the threat of the Cold War, said Madigan, a contributor to The Book of Lists: Horror and author of See No Evil and Mondo Lucha a Go-Go. Blamire’s love for these and other filmmakers of that period is evident in almost every frame shot and every line uttered, not so much as a parody but out of deference to when times were thought to be simpler, Madigan said of Cadavra. Just watch 1957’s The Astounding She-Monster to see what inspired Blamire’s sexy, black-tights-wearing vixen Animala — the stuff that fueled many pre-adolescent boys’ hormones. One secret to Cadavra’s success, according to Blamire, was the choice of a genre that naturally looked cheap — and the decision to play to that cheapness. It helped that he shared his love of low-budget sci-fi/horror flicks of the ’50s and ’60s with a circle of friends, a social network that brought talent like Fay Masterson (The Quick and the Dead, Eyes Wide Shut) and Brian Howe (Evan Almighty, Deja Vu, photo right) to Cadavra and Blamire’s subsequent films. Cadavra’s pinpoint gags and good-hearted re-creation of ’50s adventures earned it recognition as one of the top indie films of 2004 by the Independent Features Project, and Blamire and his company rode that success into their next movie, The Trail of the Screaming Forehead. The full-color production featured stop-motion animation endorsed by the legendary Ray Harryhausen. Lost Skeleton fans have pestered Blamire about the fate of Forehead, which has appeared at film festivals but failed to land a distribution deal. Without going into great detail, Blamire promised a DVD release in 2009. Following Forehead’s failure, Blamire and his corps of actors set up their own company, Bantam Street, and set to work on Lost Skeleton Returns and Dark and Stormy Night, a more-ambitious, ’30s-esque murder mystery spoof involving elaborate soundstage sets and effects by Chiodo Brothers Productions (Team America, Elf). Next, Blamire is looking forward to shooting the sci-fi adventure Voyage to the Planet of Space with yet a bigger budget. And, at some point, we’d like to take on a serious project — a dramatic story, he said.

劳里·巴拉米尔导演

Andrew Parks饰: Kro-Bar

菲夫·萨顿饰: Sangrampa

丹尼尔·洛巴克饰: Gondreau Slykes

Michael Schlesinger饰: Hupto

Robert Deveau饰: Handscomb Draile

保罗·邦内尔饰: Cheepta

费伊·马斯特森 饰: Betty Armstrong

H.M. Wynant饰: General Scottmanson

Christine Romeo饰: Sandra Fleming

Kevin Quinn饰: Carl Traeger

Alison Martin饰: Chinfa - Queen of the Cantaloupe People

布莱恩·豪威饰: Peter Fleming

劳里·巴拉米尔饰: Dr. Paul Armstrong

苏珊·迈克康纳饰: Lattis

Dan Conroy饰: Jungle Brad

Jennifer Blaire饰: Animala

John Stuart West饰: Bentivegitantus

戴维·J·肖饰: Cantina Bartender

影视行业信息《免责声明》I 违法和不良信息举报电话:4006018900